The development of architecture in the 20th century is inextricably bound up with the rise of the automobile. This history is writ large, in contemporary society, in the seemingly inexorable proliferation of fast food chains, car dealerships, and big box stores, surrounded by acres of asphalt, that line our suburban byways and highway interchanges.

But long before the somewhat dystopic present, "carchitecture" had a somewhat utopic past. Two of the most important architects of the early Modern era—Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier—were both heavily influenced in their work (though in very different ways) by the automobile; they each even went so far as to design an automobile.

Favoring individualism and the pastoral, Wright was something of an anti-urbanist, wanting to bring humans back to the land, and he saw the car as the vehicle for accomplishing this. His generally horizontal designs for single-family homes, with prominent garages and carports, reflected this orientation. They also suited America's geopolitical tendencies toward decentralization, based in no small part on the ready availability of land. Wright also saw the automobile as a means to provide recreation and escape in nature. This is notable in his design for the Gordon Strong Automobile Objective and Planetarium, featuring a mountaintop spiral-ramped viewing platform that would favor vistas from within the confines of a car. It also was seen in his grand and lifelong plan for Broadacre City, an ersatz rural "paradise", made up of single-family homes and farms tethered to roads and cars, and hostile to pedestrians. Our modern suburbs are heavily influenced by Wright.

In contrast, the European Le Corbusier (Charles Edouard Jeanneret) favored centralized and communal density, envisioning hordes of urban inhabitants dwelling in giant towers surrounded by park-like settings. He famously described buildings as "machines for living," and his designs capitalized on the streamlined mass production practices that originated in the auto industry. Instead of using cars to unshackle people from the city, Le Corbusier wanted to re-imagine "antiquated" urban centers in a way that suited and accommodated the automobile. His pet project, La Ville Radieuse (Radiant City) favored giant superhighways to transport people in and out, and giant underground garages to separate unsightly cars from resplendent parkland. Our modern urban centers are heavily influenced by Le Corbusier.

Of course, the myriad "carchitectural" designs weren't limited to the ones penned by these two. The double helix and D'Humy ramp systems of the Teens and Twenties—with their split levels and drive-in/drive-out capabilities—were among the inventions that allowed the development of the modern parking structure, solving the problem of where to put the millions of cars that streamed in and out of densely populated spaces daily. We see their ongoing influence in the spectacular 1111 Lincoln Road project, designed by architects Herzog and de Meuron in Miami's South Beach, where the parking lot itself is a destination, complete with retail establishments and stunning views. Or in the high-end New York apartment towers designed by German architect Anabelle Selldorf, which allow residents the ultimate urban luxury of being able to drive their vehicles directly into their apartments via private car elevator.

Beyond this, there is the "carchitectural" history of automotive factory design. Detroit architect Albert Kahn was perhaps the premier architect in this realm, taking Beaux Arts notions of space and decoration and translating them to industrial projects, casting them in the then-modern material of reinforced concrete. Among his many Motor City projects were the Packard Plant, Ford's River Rouge and Highland Park plants, the Fisher Body Plant, as well as the Detroit Arsenal Tank Plant and Willow Run Bomber Plants (key to America's WWII effort.) Kahn's River Rouge plant has been recently updated with a "green roof" by William McDonough + Partners, and is now the nation's largest ecologically inspired living roof, absorbing storm-water runoff and carbon dioxide.

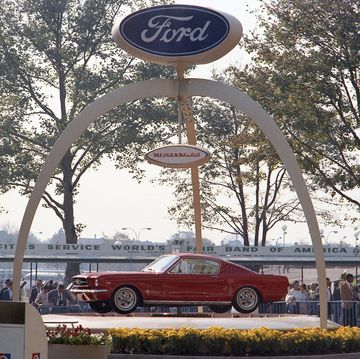

Finally, no discussion of carchitecture would be complete without further noting the aforementioned car dealerships. Established in the early 20th century, these showrooms reached their apotheotic pinnacle of glass-walled demonstration modernism in the 50s and 60s, when planned obsolescence and year-over-year model changes made the appearance of new models both a circus and a spectator sport. These automotive dioramas have since become fixtures of our exurban landscape. One of the gravest changes to arise at the national auto mall came following the financial implosion of 2008, when the domestic manufacturers restructured and closed thousands of these outposts. Many have since remained vacant, but others have been repurposed as supermarkets, churches, fitness clubs, dry-docks, tow lots, and Sheriff's department dog training facilities.

As suburban and rural populations shrink, and urban ones swell—a major demographic trend led simultaneously by the young and retired—our reliance on the automobile will continue to shift. It will be intriguing to see what grand "carchitectural" theories the 21st century brings.

The Road Ahead is a series of reports on where we've been, where we are, and where we're headed as it pertains to cars, motorsports, and the culture surrounding it all.

Brett Berk (he/him) is a former preschool teacher and early childhood center director who spent a decade as a youth and family researcher and now covers the topics of kids and the auto industry for publications including CNN, the New York Times, Popular Mechanics and more. He has published a parenting book, The Gay Uncle’s Guide to Parenting, and since 2008 has driven and reviewed thousands of cars for Car and Driver and Road & Track, where he is contributing editor. He has also written for Architectural Digest, Billboard, ELLE Decor, Esquire, GQ, Travel + Leisure and Vanity Fair.